Exploration and Survey of the Martin Ridge Cave System, Edmonson County, Kentucky

J. Alan Glennon

Excerpted from:

Glennon, J.A., 2001, Application of Morphometric Relationships to Active Flow Networks within

the Mammoth Cave Watershed, M.Sc. Thesis, Bowling Green: Western Kentucky University, 87 p.

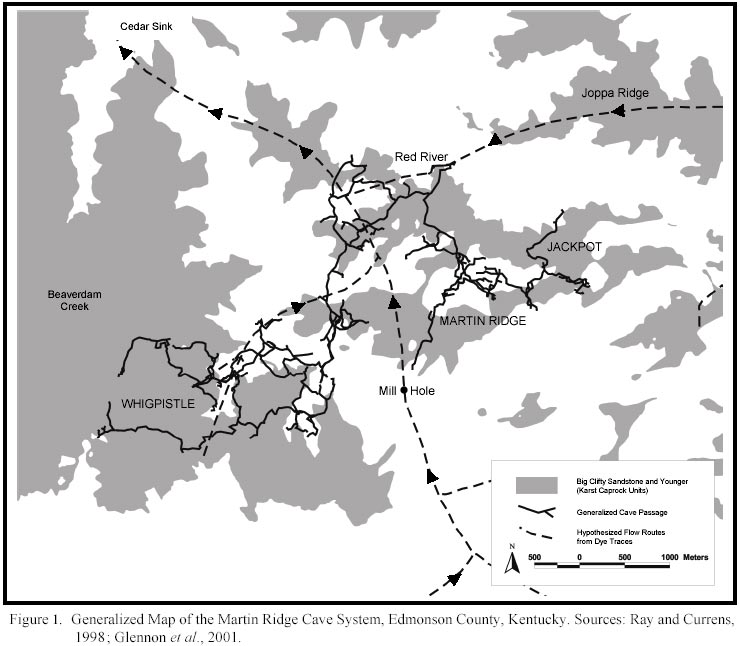

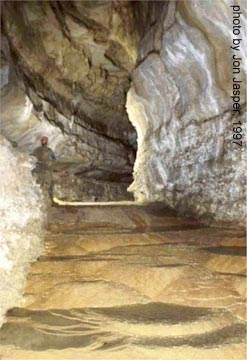

Whigpistle Cave, Martin Ridge Cave, and Jackpot Cave comprise the Martin Ridge Cave System (Figure 1). Whigpistle Cave was discovered in 1976 by Rick Schwartz of the Uplands Research Laboratory (Taylor, 1979; Kerr, 1981). In the following years, lab director Jim Quinlan hired seasonal Mammoth Cave National Park employees to map and conduct hydrologic research on the cave. Whigpistle begins at an entrance swallet and follows through low pools and streams. Ducking into the Whigpistle Cave entrance, cavers are immediately met with a still pool six decimeters deep with three decimeters of air space. Beyond the pool, the passage opens into a trunk segment four meters wide and two meters tall. An obscure side-lead off this passage drains the entrance-swallet area and can be followed through a series of crawls and canyons before it finally enlarges to comfortable dimensions. Through the late 1970s, Quinlan’s surveyors continued finding numerous creeks and sumps. Finally, a passage that had been sumped since the cave’s discovery cleared, and cavers explored beyond to the long F Survey. The F Survey extends east and then north, finally leading to the largest underground chamber in the Mammoth Cave area, the Big Womb (240 m long x 40 m wide x 13 m high). Cavers in the early 1980s found and surveyed many kilometers of cave passage including large, impressive trunks in the cave’s southern section. These trunks parallel the nearby Dripping Springs Escarpment. The first completely dry trunk, far above the cave’s flood zone, is called Yoh Avenue. The dry, tubular passageway was the exception to the cave’s many wet canyons and led both east-southeast to west-northwest for nearly a kilometer. In a nearby portion of the cave, explorers mapped beyond the Big Womb. The passageway continuing out of the Big Womb consisted of several hours of hard wetsuit caving down to low, wet levels. The passageways, however, led east toward Mammoth Cave. Among these passages, discovered in the early 1980s, was Jon’s Sump. The sump held quicksand-like mud in a low, wet crawl. Passing through Jon’s Sump was hazardous, but beyond, Quinlan’s explorers discovered a large stream passage. Later dye tracing revealed that the stream, called Red River by the explorers, was a downstream segment of Mammoth Cave’s largest stream, Hawkins River (Quinlan et al., 1990). Along the route before Red River, a side passage was surveyed. The passage was an apparent overflow tube, and at its end, a stream led east and west. The cavers hoped that by following it downstream to the west, it would lead toward another large underground river. Dye traces showed a river flowed between Mill Hole and Cedar Sink (Figure 1), and the quantity of water in Mill Hole and Owl Cave implied that the undiscovered river could be larger than Hawkins River. In 1983, though, not long after the discovery of Red River, the exploration of Whigpistle Cave ended. A large flood entirely filled Jon’s Sump with debris, so both the cave’s best lead and the Red River became inaccessible. Cave exploration in the area would be nearly nonexistent until over a decade later when another group entered a nearby, seldom-visited cave.

Jackpot Cave was known by veteran cavers Don Coons and Jim Borden, but was not seriously explored until Steve Duncan and Don Davis of the James Cave Project located the cave in the spring of 1994 (Coons, 1997a; Duncan et al., 1998). The initial sections of Jackpot Cave catered directly to cavers from the James Cave Project. James Cave is known for its technical ropework, including traversing across and down pits. Jackpot Cave called for many of these technical climbs. Systematic mapping of Jackpot began with the core group of James Cavers; for the first several months the cavers surveyed previously explored, but unmapped passages. The work continued as a strong wind let the explorers know a large cave awaited them beyond the known sections. The entrance of Jackpot Cave leads to a tall canyon where flowstone clogs the way and the cavers must wiggle though a tiny squeeze to continue. This tall canyon is also dotted with pits requiring narrow ledge traverses and technical ropework. Beyond the initial pits, the cave turns into a narrow canyon and shaft complex. At one small shaft drain, the James Cavers were able to enlarge a small opening and penetrate into virgin cave. The drain led to a series of pits and canyons requiring more technical climbing and traverses, but beyond the dig was untouched ground. The James Cavers mapped through the new cave until one tricky climb brought them to a balcony overlook above a 12-meter wide, eight-meter high passage. The PYP Boulevard was the James Cavers’ first big breakthrough. The PYP trunk continued a short direction both ways: one direction to a large pit they named “We Stop Drop”; the other to a large breakdown slope. While the pit was dropped and its shaft drain complex investigated, others in the group checked a six-decimeters high, two-meter wide crawl in the northwest wall of PYP Boulevard. Like much of Jackpot, the passage was dry, but with a “playdoh-like” mud.

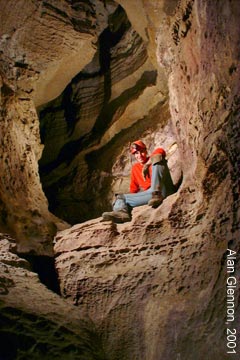

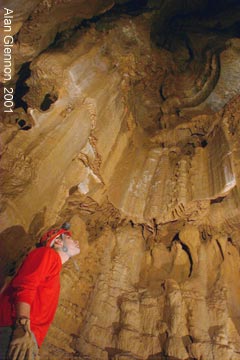

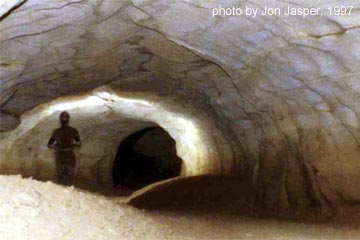

Through the crawl, the cavers found their way through small, awkward canyons to the mouth of a wide, windy bellycrawl. The crawl, called the Painful Patella, continued for 150 meters before intersecting a four-meter tall shaft and canyon. Cavers took the easiest path, climbed up, and found themselves standing in open space. They stood on the floor of a large trunk, bigger and drier than PYP. The Celestial Borehole is a trunk with average dimensions of ten meters by ten meters that continues for two kilometers. Sparkling gypsum flowers line the walls in a passage that ranks along with New Discovery, Yahoo Avenue, and Turner Avenue as the most beautiful in the Mammoth Cave region. The survey of Celestial Borehole brought Jackpot Cave to 5.2 kilometers. In spite of its size and length, Celestial Borehole yielded modest leads. With multiple traverses, technical vertical work, and numerous crawls, the number of cavers willing to explore the far reaches, including leads beyond Celestial Borehole decreased, and the exploration of Jackpot Cave slowed.

Armed with the knowledge of recent discoveries in Jackpot and the earlier discoveries in Whigpistle, Alan Glennon set out to discover a cave of his own. He recruited fellow Western Kentucky University graduate student Jon Jasper to accompany him on several of his walks. After dozens of trips searching, Alan discovered the entrance to what he later named Martin Ridge Cave on April 11, 1996. On the 11th, Jon and Alan had radios so they could communicate while searching for caves in different parts of the woods. Alan walked toward the valley bottoms and Jon at the sandstone/limestone contact near the top of the ridge. On this day, Jon and Alan had taken turns finding one small cave after another. However, all of the entrances they had found appeared to be previously known caves. While Jon was up near the ridgetop, Alan circled a low knoll in a large valley. The knoll took him past hunters’ blinds and eventually to a small, cleared field. Downed trees and debris had been pushed into a sinkhole at the field’s edge. Alan approached it, but was not sure it was worth fighting through the brush. The debris-filled sinkhole did not look promising. However, a small rock outcrop at the sinkhole’s bottom enticed Alan to investigate further. While looking for a safe way down from above, some of the brush gave way under his feet, sending him falling about one meter through debris. He climbed back up and circled the sink to find an easier and safer way down.

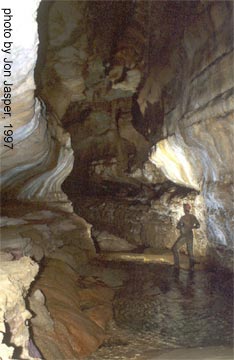

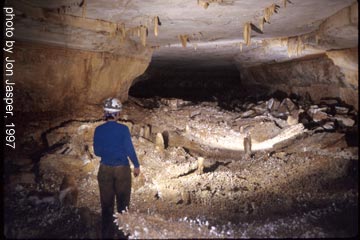

Alan found that most of the sinkhole was lined with vertical banks or dense brush. One small area of the sinkhole had a steep mud bank that could be traversed. He climbed down the mud bank, using tree limbs and brush for handholds. At the bottom, the sink was flat. A wall of debris was on one side and the other was a small rock cliff. One small hole at the bottom of the cliff acted as the drain, but was clogged with mud and debris. A horizontal crack a meter above did not look promising either. Disappointed, Alan turned toward the mudbank to climb up when he was met with an unusual blast of cold air. Alan took another look around. The only place it could be coming from was the horizontal crack. Upon further inspection, the crack was the definite source of the air, and better yet, it looked like it would be possible to dig it open enough to enter. With a potential cave to enter, Alan made a call on his radio to Jon. A few minutes later as Alan began to dig, Jon climbed down the sinkhole to assist. It did not take long to make the hole big enough to enter, so Jon crawled in to check it out. As he investigated, Alan continued to enlarge the entrance and dug foot-steps in the sinkhole’s mud bank. All within voice range, Alan could hear Jon squirming and moving rocks inside the cave. Jon finally announced from fifteen meters inside the cave that the passage was silted up and he was returning. All the while, Alan continued to clear rocks and stabilize the entrance. As Jon headed toward Alan, Jon noticed a small vertical passage below him. Moving a couple of rocks might give him a better look. Jon moved one heavy, thin slab revealing a porthole down into a small passage. Jon yelled to Alan that he was checking out this lower passage and slipped down the porthole. Alan heard the squirming and grunting grow more distant until he could not hear it any more. Inside the cave, at the bottom of the porthole, Jon found a tight crawl that led into the distance. He crawled through the tight canyon that after six meters led to a large rock that he had to squirm around. On the other side of the rock, the cave got larger. The cave widened to two meters and was nearly a hands-and-knees crawl. He followed the passage beyond some soda straw formations on the ceiling and a small climb down to a crawling maze. Crawlways headed in a number of directions, but the way to go was clear. Straight ahead led to a hole in the floor and beyond, a canyon six meters high and a meter wide. He climbed down, heard water and investigated. A hole in the floor of this canyon led to a passage two meters high and two meters wide with a small stream along its floor. He walked a bit to follow the stream. It did not flow far. After twenty meters, the stream began dropping a series of small waterfalls and the passage got narrower. Jon followed the stream until his encountered a seven-meter cascade. It was too far down to climb. Jon noticed that as the waterfall dropped, instead of a canyon, the walls diverged far to the left and right, and ahead was blackness. Jon stared into the open space of a large trunk, twelve meters wide and ten meters tall. Jon turned around, went back up the creek, up the climbs, through the crawls, and found Alan with his head poked slightly in the entrance awaiting news of whether the cave went or not. Jon returned and told of his discoveries. With the possibilities of new and significant discoveries, they decided to share their new cave with a close-knit group of friends.

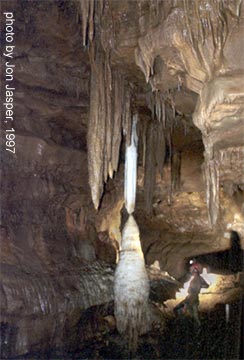

The following days, Jon and Alan began the cave’s survey. Down the waterfall, the passage did not go far, but a crawlway was discovered that led to a thirty-meter pit intersecting a significant stream. The creek’s tall canyon intersected other passageways, and Alan and Jon furiously mapped the new discoveries. One muddy and wet crawlway above the stream canyon led to a dry, elliptical trunk. Called Dreamland Trunk, the passage averages eight meters wide and two meters high. After heading east for 600 meters, Dreamland Trunk overlooks a tall canyon. The fifteen-meter tall, four-meter wide Overlook Avenue is only 400 meters in length, but is decorated with beautiful travertine dams and a tall white column. Furthermore, the northern end of Overlook Avenue, Jon and Alan discovered the bottom of a domepit. While investigating the dome, Jon discovered footprints. On June 24, 1996, Jon and Alan had connected with Jackpot Cave. The connection took place at a lead beyond the Celestial Borehole in Jackpot Cave. The connection point, a pit called Cold Well, was far away from both the Jackpot and Martin Ridge entrances. Like their cave, Alan and Jon kept their connection secret too.

By the beginning of July 1996, only six people had entered the Martin Ridge Cave entrance, including Russell Conner, Chris Groves, Marc Ohms, Art Pettit, Jon Jasper, and Alan Glennon. These six went on to map 6,500 meters and discover several trunks; however, much of the cave tended to be narrow, tall canyons. The canyons continued, occasionally intersecting other canyons, but also breaking down and silting shut. Many of the cave’s passageways contained small streams that drained the overlying valley. Alan and Jon named the largest stream in the cave Quinlan Creek, after the late Jim Quinlan. Following Quinlan Creek, the water reached nearly to the ceiling. Alan passed through the near-sump, but the passage on the other side became a crawl and seemed likely to hit another sump before too long. Alan and Jon decided to leave this low wet passage for late August, when they would have the best chance of finding sumps cleared and the lowest chance of being trapped by rising waters. As the end of August approached, the number of promising leads diminished. Jon and Alan spent time mapping small crawls and canyon “cutarounds.”

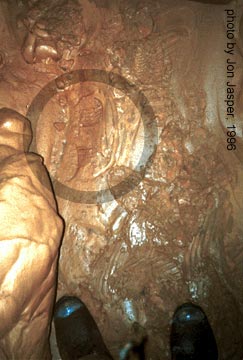

In August, after a “mop up” trip, they decided to take another look at the near-sump. They jumped in the water and passed through the sump to where it opened up again. The passage continued as a hands-and-knees stream crawl, but because the ground was stone cobbles and gravel, a sump ahead did not appear imminent. Thirty meters beyond the spot Alan had previously turned around, the cave began getting larger. The cavers were able to walk upright, and the passage slowly took the dimensions of 2.5 meters by 2.5 meters. They walked for several hundred meters before reaching a side lead. The side lead was large, so they decided to take a quick look. Upon entering the side passage, Jon stopped. He saw a footprint. Alan saw it too. It looked like a footprint, but it was the only one. They looked for other marks, scuffs, footprints, or survey stations, but could find nothing. Maps showed the near-sump to be at least two kilometers from known passageways in Whigpistle Cave, and they did not know of any other major caves to the west of their entrance. Jon continued to believe the mark was a footprint, while Alan was not so sure.

A couple of days later, Jon and Alan obtained the survey notes of Whigpistle Cave. Alan immediately thumbed to the last page of the survey. The sketch looked exactly like the intersection where the footprint was. Was that mark a footprint from someone from the Whigpistle side? If so, the Whigpistle group was comprised of Mike Summers, Chris Kerr, and Geary Schindel. Geary had been a graduate student at Western Kentucky University Center for Cave and Karst Studies, like Alan and Jon, only thirteen years earlier. Two days later, Alan, Jon, and Chris Groves went into Martin Ridge to survey the new discoveries. A map of the stream would answer the question of whether this was Whigpistle Cave. The survey began at Quinlan Creek’s near-sump and continued to the side-lead. The survey added 914 meters to the length of the Martin Ridge-Jackpot Cave System. While surveying at the side-lead, the surveyors discovered a mud-covered pokerchip that had been left as a survey marker thirteen years prior. Chip 89 was left at the end of Summer Avenue in Whigpistle Cave. On August 24,1996, the Martin Ridge cavers had connected to Whigpistle Cave, the system was now over 47 kilometers long, and one of the longest caves in the United States.

The weekend after the Whigpistle Cave connection, cavers in Jackpot Cave discovered foreign survey marks in the vicinity of Cold Well. Knowing that Alan and Jon had been mapping small caves in the area, the James Cavers contacted Alan and Jon. The groups each made their new caves and connections known. Don Coons, the primary surveyor of Whigpistle Cave, the James Cave Project, and the Martin Ridge Cavers, had to decide on the name of this new system. Don Coons and the James Cavers suggested Martin Ridge Cave System would be the most appropriate name.

Since its disclosure, the James Cavers have regained interest in the streams and leads of Jackpot Cave. Martin Ridge Cavers have surveyed an additional six kilometers, including large trunk passageways. Whigpistle Cave holds many leads that await persistent surveyors (Coons, 1997b). The new discoveries and connections have the explorers’ looking toward the northeast. Mammoth Cave is only two kilometers away. Currently, the Martin Ridge Cave System is the United States' tenth longest cave-- and Kentucky’s third longest, at 52.6 kilometers.

Update: As of February 2019, the Martin Ridge Cave System is 55.7 km long and the 13th longest in the United States. The James Cavers have dug a new artificial entrance into Jackpot Cave. The survey of the Whigpistle and Martin Ridge sections is led by explorers from the Cave Research Foundation.

REFERENCES

Coons, D. Interview with the author. 1997a.

Coons, D. Whigpistle Cave Map. 1997b.

Duncan, R.S., Currens, J., Davis, D., & Eidson, W., 1998, Trip Reports and Cave Descriptions of Jackpot Cave. E-mail correspondence with the author from 1996-1998.

Glennon, J.A., Groves, C.G. & Coons. D., 2001, Martin Ridge Cave System, Talk presented at 2001 National Speleological Society Convention, U.S. Exploration Session, Great Saltpeter Cave Preserve, Kentucky.

Kerr, C., 1981, Whigpistle Saga, Speleotype, vol. 14(1), pp. 4-12.

Quinlan, J.F., Ewers, R.O., & Palmer, A.N., 1990, Hydrogeology and Geomorphology of the Mammoth Cave Area, Kentucky, 1990 Field Excursion. Southeastern Friends of the Pleistocene: 102 p.

Ray, J.A. & Currens, J.C., 1998, Mapped Karst Ground-Water Basins in the Beaver Dam 30 x 60 Minute Quadrangle, Kentucky Geological Survey.

Ray, J.A. & Currens, J.C., 1998, Mapped Karst Ground-Water Basins in the Campbellsville 30 x 60 Minute Quadrangle, Kentucky Geological Survey.

Taylor, R.L., 1979, Discovery in Whigpistle Cave, Kentucky, The Ozarks’ Underground, vol. 1, pp. 4-7.

----- last updated: 27 February 2019 -----